Hongtong Great Pagoda Tree Ancestor Worship and Root-Seeking Tourist Area

I. Introduction

The Hongtong Great Pagoda Tree Ancestor Worship and Root-Seeking Tourist Area is located in Hongtong County, Shanxi Province. It is the only national folk worship sacred site themed around "root-seeking" and "ancestor worship." The scenic area is divided into five main thematic zones: the "Immigrant Historical Site Area," the "Ancestor Worship Activity Area," the "Folk Culture Tour Area," the "Fen River Ecological Area," and the "Root Ancestor Culture Square." It features over 60 scenic and cultural attractions, including the Stele Pavilion, the second and third-generation Great Pagoda Trees, the Millennial Pagoda Tree Root, the Ancestral Worship Hall, Guangji Temple, the Stone Sutra Pillar, the Immigrant Relief Sculpture, and the Chinese Surname Garden.

II. Immigration History

Background of Immigration

Politically

The large-scale warfare and famines in the late Yuan Dynasty destroyed the extensive land ownership system of the Yuan era. Coupled with the backward production methods of the Yuan Dynasty, much of the land in northern regions became barren. After the Mongols entered the Central Plains, the slave owners, known for plundering populations, gradually transformed into feudal landlords who annexed land. Their primary tools for annexation were the whip and the sword. They did not even use contracts; instead, they would ride their horses to encircle land, claiming it as their own. Under the heavy exploitation by officials, landlords, and usurers, the people of the Yuan Dynasty suffered greatly.

Economically

During the late Yuan and early Ming periods, the people of the Central Plains not only endured the calamities of war but also suffered from floods, droughts, locusts, and epidemics, with severity surpassing that of any previous dynasty. Additionally, decades of warfare left the people either dead or displaced, resulting in vast stretches of barren land and sparse populations in the Central Plains. Many once-prosperous areas became overgrown with thorns and covered in scars.

Culturally

Ethnic oppression has always existed in Chinese feudal society, but the cruelty of ethnic oppression during the Yuan Dynasty was particularly rare. To maintain their rule, the Mongol rulers politically divided the various ethnic groups into four classes, in descending order: Mongols, Semu people (various Central Asian ethnicities), Han people (Northern Chinese), and Southerners (Southern Chinese). The Mongols were the first class, receiving the most preferential treatment; the Semu people were the second class, next in line and also a class relied upon by the rulers. During the Yuan Dynasty, whether among the ruling or the ruled ethnic groups, there existed a class with the lowest status and most tragic fate, known as the "Qukou" (driven mouths). By the late Yuan Dynasty, due to famine and disasters, class contradictions intensified, yet they erupted in the form of ethnic struggles. Peasant uprisings spread across the land, with the Red Turban Army being the most prominent.

Causes of Immigration

After the wars of the late Yuan Dynasty, the national household registration sharply declined. Besides those who died in wars and famines, many residents fled to other regions, becoming refugees. This led to a significant decrease in the registered population and an uneven distribution of people across different areas. Provinces in the north, northwest, and the Huai River regions saw notably sparse populations. Shanxi, with its geographical advantages and less impact from the wars, had a relatively concentrated population. Therefore, it was decided to carry out immigration from Shanxi.

Immigration Policies

During the Hongtong Great Pagoda Tree immigration period, the Ming government implemented measures to encourage agricultural production by providing immigrants with oxen, seeds, farming tools, and tax exemptions for 3-5 years. Uncultivated land near cities in the north was distributed to landless people for reclamation, with each person receiving 15 mu of land and an additional 2 mu for vegetables. "Those with surplus labor were not limited by acreage."

In the 27th year of the Hongwu reign (1394), the Ming government issued an edict for additional land reclamation that would never be taxed, stipulating that immigrants in Shandong, Henan, Hebei, and Shaanxi, besides the land subject to taxation, could own any reclaimed land without ever being taxed.

Sources of Immigrants

According to the "Shanxi Tongzhi" (General Annals of Shanxi), from the first year of Hongwu (1368) to the fifteenth year of Yongle (1417), most of the relocated people came from southern Shanxi, followed by several counties in southeastern and central Shanxi. In the early Ming Dynasty, Shanxi Province administered 5 prefectures, 3 directly subordinate subprefectures, 16 scattered subprefectures, and 79 counties. Historical records indicate that early Ming immigrants mainly came from 28 counties under Pingyang Prefecture, 8 counties under Lu'an Prefecture, 7 counties under Fenzhou Prefecture, 4 counties under Zezhou, 2 counties under Qinzhou, and 2 counties under Liaozhou. These areas totaled 51 counties, with Pingyang Prefecture alone covering 28 counties.

Since the Ming Dynasty's large-scale immigration procedures were conducted under the Great Pagoda Tree in front of Guangji Temple in Hongtong County, Shanxi—the starting point of the migration—this immigration is called the Hongtong Great Pagoda Tree immigration. However, the vast majority of people who migrated from here were not from Hongtong County, and some were not even from Shanxi.

Destinations of Immigrants

From the first year of Hongwu (1368) to the fifteenth year of Yongle (1417), spanning three reigns over 50 years, historical records such as the "History of Ming" and "Veritable Records of Ming" document a total of 18 migrations from Shanxi: 10 during the Hongwu period and 8 during the Yongle period. These immigrants spread across 18 provinces and cities, over 500 counties, involving 1,230 surnames.

Results of Immigration

Increase in Household Registration

According to the "Geography Annals of Ming History" and "Continued Examination of Historical Documents, Volume 13," the national household registration in the fourteenth year of Hongwu (1381) was 10,654,362 households with 59,873,305 individuals. By the twenty-sixth year of Hongwu (1393), the national figures were 56,052,860 households and 60,545,812 individuals. Over 12 years, households increased by 5,398,498, and individuals by 672,507. The population increase was particularly evident in areas settled by Hongtong Great Pagoda Tree immigrants.

Reclamation of Farmland

According to the "Biography of Zhu Yuanzhang," from the first year of Hongwu (1368) to the thirteenth year of Hongwu (1380), the amount of reclaimed land increased from over 770 qing to 53,930 qing. In the fourteenth year of Hongwu, the national cultivated land was 3,667,715 qing, with a total reclamation area of over 1.8 million qing in the preceding eleven years. According to the "Veritable Records of Ming Taizu, Volume 140," by the twenty-sixth year of Hongwu (1393), the total national farmland had increased to 8,567,623 qing. This far exceeded the cultivated land area since the Song and Yuan dynasties, representing a fourfold increase compared to the total cultivated land in the first year of Hongwu. On average, each person could own 17 mu of farmland. Notably, Henan, Shandong, and Hebei saw significant reclamation by Hongtong Great Pagoda Tree immigrants.

Increase in Grain Production

According to the "Veritable Records of Ming Taizu, Volume 176," in the eighteenth year of Hongwu (1385), the national income of wheat, rice, and beans was 20,809,617 dan. By the twenty-sixth year of Hongwu (1393), this had increased to 32,789,800 dan, doubling the Yuan Dynasty's annual tax grain income of 12,114,700 dan. By the end of the Hongwu period, the grain submitted by military colonies was only 5 million dan, but by the Yongle period, it had reached 2,300 dan. On average, each household produced over 50 dan of grain and over 1,900 jin of cotton. These 598 immigrant households cultivated over 13,380 qing of land, averaging 22 qing per household. If all the land were used for grain, each qing could yield around 200–300 dan, with a per-mu yield between 2–3 dan, which was quite high for the time.

III. Main Attractions

Root Carving Gate

The "Root Carving Gate" is the main entrance of the Root-Seeking and Ancestor Worship Park. Designed in the shape of a pagoda tree root, it spans 20 meters east to west and stands 13 meters high. Its ancient, weathered, majestic, and sturdy appearance, with roots deeply embedded in the soil, symbolizes the descendants of the Great Pagoda Tree sharing the same gate, roots, ancestors, and heart. It represents the children of the Great Pagoda Tree leaving their small homes for greater righteousness, taking root across the divine land of China, and tirelessly laboring and striving for the nation's prosperity and the ethnic group's flourishing. It诠释s the common roots and ancestral home of the immigrant descendants, embodying the soul of the Great Pagoda Tree's children.

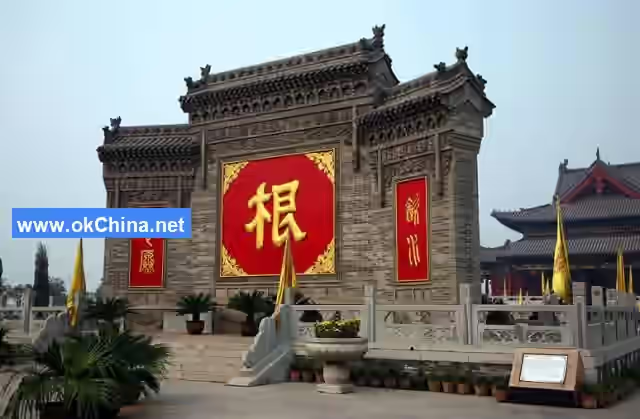

Root Character Screen Wall

The screen wall is a landmark feature of the scenic area. This large clerical script character for "root" (根) was inscribed by Mr. Zhang Ding, the former president of the Central Academy of Fine Arts and a renowned calligrapher and painter. The character is vigorous, steady, dignified, subtly pictographic, and profound in meaning. It is imbued with deep hometown affection and a lingering sense of nostalgia, fully expressing the complex feelings of homeland and country that gather in the hearts of returning wanderers.

Stele Pavilion (Site of the Ancient Great Pagoda Tree)

The Stele Pavilion is built on the site of the first-generation Great Pagoda Tree. The stele is about 3.5 meters high and over 0.8 meters wide. The stele crown features the seal script characters for "commemorate" (纪念) amidst fine dragon carvings. The front of the stele is engraved with the five clerical script characters "古大槐树处" (Site of the Ancient Great Pagoda Tree). These characters were not written with a brush but with a刷子. It is said that one of the builders of the site, Liu Zilin, had a very poor friend who could not afford to donate money for the pavilion's construction. He could only write the characters with a刷子 and did not leave his name. Despite not donating money, his calligraphy was excellent and was thus adopted.

Second and Third-Generation Great Pagoda Trees

This is the second-generation Great Pagoda Tree, sprouted from the first-generation ancient tree, with a history of nearly 400 years. The third-generation Great Pagoda Tree, sprouted from the same roots as the second-generation tree, also has a history of nearly a hundred years. When immigrants bid farewell to their homeland, they all regarded the Great Pagoda Tree as a symbol of their hometown. After settling in new lands, they planted pagoda trees in their courtyards and hung auspicious objects to pray for the protection of their homeland and to express their longing for it.

Millennial Pagoda Tree Root

According to archaeological appraisal, this root grew during the Song and Yuan periods, approximately 1,000 years ago, long before the early Ming immigration. The pagoda tree root is 6.2 meters tall, with 4.2 meters exposed above ground. The root is gnarled and intricately intertwined, with a peculiar shape that inspires rich associations. It is a rare large ancient pagoda tree root.

Immigrant Relief Sculpture

Three sets of relief sculptures, with the Great Pagoda Tree as the background, depict from left to right: the National Immigration Policy, the Immigrants' Farewell, and the Immigrants' Migration. Text separates the scenes, explaining the images and complementing each other. They specifically narrate the causes of the Great Pagoda Tree immigration, the people of the Pagoda Tree homeland parting from their native land, and scenes from their migration journey.### Immigration Scenes Sculptures Through three sets of immigration scene sculptures—Court Resolution, Under the Great Pagoda Tree, and The Never-Ending Story—the immigration history under the Great Pagoda Tree is vividly depicted. The first set of sculptures shows Zhu Yuanzhang listening to the proposals of his court ministers and ordering the start of the migration, known as the Court Resolution. The second set portrays an elderly person under the Great Pagoda Tree bidding a reluctant farewell to their children. The third set, The Never-Ending Story, depicts the young man who migrated long ago now as an elder, still recounting the migration story to his descendants.

Ancestral Worship Hall

The Ancestral Worship Hall, designed and constructed by the Shanxi Provincial Institute of Ancient Architecture Preservation, features an architectural style imitating the Ming Dynasty and serves as the core of the entire Ancestral Worship Garden. The hall faces south, with a width of 112 meters, a depth of 55 meters, and a total area of 6,160 square meters. In front of the hall stands an open-air bronze incense burner, while inside, 1,230 ancestral tablets of migrant families are enshrined. This not only reflects traditional culture but also highlights the theme of "ancestral worship." It is the largest ancestral hall of Chinese surnames in the country and the foremost hall for public ancestral worship in the world.

Homeland Viewing Pavilion

Located east of the Ancestral Worship Hall, the Homeland Viewing Pavilion is a place dedicated to welcoming returning visitors from afar. Its serene environment and simple layout allow visitors to savor a cup of hometown water and browse books about the Great Pagoda Tree migration. All services in this tea room are free of charge. As the old tea room could no longer meet the growing needs of returning visitors, this new tea room was established, serving the same purpose and significance as the original. Offering a cup of tea and a ladle of water to descendants who travel thousands of miles to trace their roots and worship their ancestors expresses the heartfelt affection of the hometown people. Treating guests with tea is a noble ritual with profound cultural significance, and using hometown water and tea to welcome fellow townspeople holds extraordinary meaning.

Offering Hall

The Offering Hall is used for placing offerings during worship ceremonies and serves as the main activity area for officiants. Located on the central axis of the ancestral worship area, it covers a building area of 1,250 square meters, with five bays in width and depth. It features a single-story double-eave design, surrounded by corridors on all four sides, and is constructed in the style of a Ming Dynasty all-wooden structure. Its cross-gabled roof is integrated with a Ming-style opera stage, making it the tallest and widest of its kind in Shanxi. Its magnificence and grandeur are rare nationwide.

Origin Tracing Pavilion

Located west of the Ancestral Worship Hall and symmetrically opposite the Homeland Viewing Pavilion, the Origin Tracing Pavilion is the western pavilion of the main architectural complex "One Hall, Two Pavilions" of the Great Pagoda Tree. Its design imitates an ancient four-corner pyramidal roof with three eaves and two stories. The upper floor is connected to the Ancestral Worship Hall by a climbing corridor. The name "Origin Tracing" signifies tracing the historical facts of migration and remembering the virtues of ancestors. The overall layout of the pavilion emphasizes the theme of tracing migration history and showcasing hometown culture.

Chinese Surname Garden

The Chinese Surname Garden is primarily composed of displays on the origins and evolution of Chinese surnames, featuring 11,969 surnames, along with cultural elements such as ancestral halls, hall names, couplets, and family mottos. Here, visitors can immerse themselves in a feast of Chinese surname culture.

Migration Evidence Exhibition Hall

This hall features clay sculpture groups depicting migration scenes, daily utensils used by migrant ancestors, and numerous precious migration genealogies. Each artifact on display tells a touching story. Though they may appear ordinary, they serve as the most authentic witnesses and precious evidence of migration history.

Guangji Temple

The Guangji Temple in Hongtong County was built in the second year of the Zhenguan era of the Tang Dynasty. Its original location was in Yong'anli, Hongtong City, and it was relocated to the banks of the Fen River in Jiacun Village during the Jin Dynasty's Cheng'an era. In its heyday, Guangji Temple was grand in scale, with numerous monks and thriving incense offerings. It included halls such as the Heavenly King Hall, Mahavira Hall, Three Saints Hall, Dharma Hall, Sutra Library, Sangharama Hall, Patriarch Hall, Meditation Hall, Abbot's Quarters, and Bell and Drum Towers, as well as a dining hall, guest hall, dormitory, tea house, and Longevity Hall. To the left of the temple gate stood a large pagoda tree that provided shade over several acres—the very tree that became unforgettable during the early Ming migration for handling official affairs.

Pagoda Tree Fossil

The pagoda tree fossil was excavated from a coal mine in the western mountains of Hongtong. According to expert research, it dates back hundreds of millions of years. Many parts of the fossil have already carbonized, vividly illustrating that pagoda trees existed in Hongtong as early as hundreds of millions of years ago. Thus, Hongtong truly deserves its title as the "Land of Pagoda Trees."

Stone Sutra Pillar

The Stone Sutra Pillar is the oldest artifact in the Ancestral Worship Garden and the only historical witness to the Ming Dynasty migration still in existence. Sutra pillars are a type of ancient Buddhist stone carving that originated in the Tang Dynasty. They are constructed from multiple stone blocks stacked into a column, with a disc-shaped cover on top and Buddhist scriptures and images carved on the body. This pillar was built in the fifth year of the Cheng'an era of the Jin Dynasty (1201) by Master Huilian of Guangji Temple, predating the migration by over 200 years. It is the only relic of Guangji Temple and a typical example of sutra pillar art, with a history of over 800 years. Made of bluestone, it is octagonal in plan, with four layers and fifteen levels, standing 9.4 meters tall. Its carving art is simple yet profound, the calligraphy vigorous and fluid, and the reliefs lifelike, making it a treasure of Jin Dynasty carving art.

Passage Hall

This Passage Hall features five bays, three openings, and one entrance. The gatehouse is topped with glazed tiles, complete with decorative ridge beasts, and two seven-character quatrains are inscribed under the central eave. The first poem means: All descendants of migrants are "Hongtong people" from Yanghou Kingdom, which is not unfounded, as numerous private inscriptions and genealogies record this. The second poem means: Descendants of migrants in Beijing, Henan, Shandong, and the Chuzhou and Hefei areas of Anhui share the same roots and origins. There is no need to worry about mistaken identities, as the ancient legend of the split little toe serves as proof of recognition.

Hongya Ancient Cave

The construction of Hongya Ancient Cave here is deeply connected to Hongtong, as the name "Hongtong" is derived from "Hongya" in the south of the city and "Ancient Cave" in the north. The eight large characters "洪崖堑壁" (Hongya Steep Cliff) and "古洞连云" (Ancient Cave Touching the Clouds) were written by the famous calligrapher Dong Shouping. The Hongya Ancient Cave covers an area of 800 square meters, measuring 40 meters from north to south and 20 meters from east to west. The cliff is 16 meters high, while the cave is 4 meters high and 2.5 meters wide, with winding passages inside.

Folk Village

Although the threshing ground here no longer showcases the lively scenes of migrant ancestors threshing, winnowing, and packing wheat, it features tall stacks of wheat, stone rollers that only strong men could push, swings for children to play on, and local Hongtong snacks, offering a unique taste of hometown charm. The furniture in the Ming Dynasty courtyard of the Folk Village is exquisite, reflecting the homes of wealthy families of that time. The Wedding Courtyard represents the homes of ordinary people, with ancient wedding costumes available for photos. The Craftsmen's Courtyard depicts the homes of families with below-average living standards, featuring simple architecture. The Cultural Revolution Courtyard, with its fence walls, recreates rural family life during the Cultural Revolution. The Weaving and Knitting Courtyard showcases the distinctive weaving and knitting crafts of Hongtong farming families in a spacious layout. The Farmer's Cart Courtyard focuses on the production and daily life scenes of cart operators during the Republic of China era, exuding local charm. The Doctor's Family Courtyard displays the tile-roofed architectural style unique to southern Hongtong. The Ordinary Farmer's Courtyard, with its simple and practical furnishings, reflects the living conditions of ordinary Hongtong farming families in the early 1950s.

Kuixing Tower

The tower-shaped building at the southernmost end of the Folk Village is the Kuixing Tower. According to the Book of Han, Kuixing is a "deity" in ancient mythology who governs literary fortunes. The Kuixing Tower was a sacred place in ancient villages where scholars worshipped Kuixing, praying for success in imperial examinations. The phrase "Kuixing selects the top scholar" originates from this. Next to the Kuixing Tower, the Big Dipper is also depicted. The first four stars of the Big Dipper are called "Xuanji," also known as Kuixing, and because they are arranged like the character "斗" (dipper), they are also called "Doukui."

Common Origin Canal

As the name suggests, the Common Origin Canal signifies that descendants of migrants share a common origin. Though scattered across the country and integrated into the broader Chinese nation, their origin is singular—the Great Pagoda Tree of Hongtong. As long as they are descendants of the Great Pagoda Tree, they can trace the footsteps of their migrant ancestors here and find family members who share the same roots.

Source Reflection Pond

No matter how far water flows, it always has a source; no matter where people reside, they never forget their homeland. When migrant ancestors set out from here to explore new lands, they never forgot their longing for their hometown. Centuries later, their descendants will not let time diminish their attachment to their origins. Here, you can silently reflect on ancestral grace, cleanse your hands, and worship your ancestors with a devout heart.

The First-Generation Great Pagoda Tree (Replica)

The newly sculpted Great Pagoda Tree is based on historical records of the ancient tree, recreating its grandeur. According to records, the original tree had a circumference of "seven arm spans plus one woman's arm span," meaning it took seven men and one woman holding hands to encircle it. With one man's arm span measuring five feet and one woman's arm span measuring 4.5 feet, the replica tree has a circumference of nearly 40 feet and a diameter of 13 feet.

Memorial Archway

This memorial archway was built in the third year of the Republic of China (1914). Its front and back plaques are inscribed with "誉延嘉树" (Fame Extends to the Fine Tree) and "荫庇群生" (Sheltering All Living Beings). "Fame Extends to the Fine Tree" refers to the Great Pagoda Tree's renowned reputation at home and abroad as its descendants migrated far and wide. "Sheltering All Living Beings" means the tree's spirit has protected migrant descendants and all beings under its shade for generations. During the Xinhai Revolution, the Land of Pagoda Trees was spared a major catastrophe thanks to the Great Pagoda Tree.### Tea House The Tea House is constructed with a fully wooden frame structure, standing 11 meters tall, 23.65 meters long from north to south, and 13 meters wide from east to west. The first floor features purely green, pollution-free agricultural products characteristic of Hongtong, while the second floor houses a teahouse styled after the Ming Dynasty. More than just a traditional folk building, the Tea House is a vivid embodiment of the age-old Chinese custom of welcoming guests with tea in Hongtong. It offers the most authentic experience of the warm hospitality and simple, honest folk customs of the ancestral homeland.

Tea Room

Built in the third year of the Republic of China, the Tea Room is a dedicated space for visitors to rest, enjoy tea, and chat. It measures 10.45 meters in width and 4.77 meters in depth, with a modest area and an average ridge height. While its appearance resembles that of a typical residence, its significance is extraordinary. It was specifically constructed to welcome back those returning from afar. The inscribed plaque and couplets express the deep familial bond between the ancestral home and its returning visitors.

Three Bridges

- West Bridge: Named Lianxin Bridge (Lotus Fragrance Bridge), it carries two meanings. First, Hongtong has long been celebrated as the "Lotus City." Historically, the county town was elevated while the surrounding areas were lower, allowing people to store water and cultivate lotuses. In summer, the fragrance of lotus flowers would permeate the entire city of Hongtong, truly embodying the phrase "water surrounds the base, a city of lotuses." Second, "Lianxin" is a homophone for "heart-to-heart," symbolizing the eternal bond between the people of the ancestral home and the descendants of emigrants.

- Middle Bridge: Named Huaixiang Bridge (Locust Fragrance Bridge), it also holds two meanings. First, this area is the homeland of locust trees, where the fragrance of locust blossoms fills the air. Second, "Huaixiang" is a homophone for "huai" (cherish) and "xiang" (hometown), signifying that the descendants of the Great Pagoda Tree forever cherish their ancestral homeland.

- East Bridge: Named Guanming Bridge (Stork's Call Bridge), it borrows the call of the stork to express the homesickness of those far from home. You may have heard this folk rhyme: "Ask where my ancestors are from, the Great Pagoda Tree in Hongtong, Shanxi. What is the name of our ancestral home? The old stork's nest under the Great Pagoda Tree." The "old stork" in the rhyme refers to a waterbird resembling a crane but with a shorter neck and body. They were often seen foraging in large flocks along the Fen River and building massive nests in the Great Pagoda Tree.

IV. Ancestral Worship Festivals

First Hongtong Great Pagoda Tree Root-Seeking and Ancestral Worship Festival

In April 1991, the first Hongtong Great Pagoda Tree Root-Seeking and Ancestral Worship Festival was held. As the tide of reform surged, activities centered on the "Root and Ancestor Culture," embodied by the ancient Great Pagoda Tree emigrant site, became unprecedentedly active and flourished. Across the nine regions of China and even among descendants of the Great Pagoda Tree overseas, the longing to return to their roots and the wave of homecoming for ancestral worship grew stronger each day. To align with this historical trend, the Hongtong County Committee and County Government, under the principle of "culture sets the stage, economy performs," organized the first Hongtong Great Pagoda Tree Root-Seeking and Ancestral Worship Festival.

Seventeenth "China · Hongtong Great Pagoda Tree Root-Seeking and Ancestral Worship Ceremony"

In April 2007, the seventeenth "China · Hongtong Great Pagoda Tree Root-Seeking and Ancestral Worship Ceremony" was jointly hosted by the Shanxi Provincial Government and the Linfen Municipal Government, making it the largest such event in history. Media outlets including CCTV News Channel, Phoenix TV, and Shanxi Television broadcast the ceremony live. Renowned hosts Wu Xiaoli from Phoenix TV, Zhu Jun from CCTV, and Li Liping from Shanxi Television presided over the event. Famous singer Tan Jing performed the song "Great Pagoda Tree," expressing people's boundless affection for the tree, while Yan Weiwen's live rendition of "Mother" conveyed the heartfelt emotions of Chinese descendants worldwide. Former Vice Governor of Shanxi Province Song Beishan presided over the grand ceremony. Li Meng, Vice Chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, and his wife presented a floral basket to the ancestors. Huang Dawei, a prominent figure and nephew of the famous patriotic general Zhang Xueliang, traveled from afar to deliver a speech expressing his grandfather's lifelong nostalgia for his hometown. This Root-Seeking and Ancestral Worship Festival garnered significant resonance among Chinese communities globally.

Past Root-Seeking and Ancestral Worship Festivals

Since 1991, each Hongtong Great Pagoda Tree Root-Seeking and Ancestral Worship Festival has attracted tens of thousands of descendants of Great Pagoda Tree emigrants, who gather to express their profound love and deep affection for their ancestral homeland. Party and state leaders such as Jiang Zemin, Qiao Shi, Li Changchun, Liu Yunshan, and Liu Yandong, as well as renowned figures from various sectors including Jia Pingwa and Zhang Yufeng, have visited the Great Pagoda Tree Root-Seeking and Ancestral Worship Park. They have participated in root-seeking and ancestral worship activities, leaving behind inscriptions, calligraphy, and messages.

Comments

Post a Comment