Xi'an City Wall · Forest of Stone Steles Historical and Cultural Scenic Area

I. Introduction

The Xi'an City Wall · Forest of Stone Steles Historical and Cultural Scenic Area, abbreviated as the Xi'an City Wall · Forest of Stone Steles Historical and Cultural Scenic Area, is located in the Beilin District of Xi'an City, Shaanxi Province.

The Xi'an City Wall · Forest of Stone Steles Historical and Cultural Scenic Area consists of the Xi'an City Wall Scenic Area and the Xi'an Forest of Stone Steles Museum. The Forest of Stone Steles was initially established in the second year of the Yuanyou era of Emperor Zhezong of the Northern Song Dynasty (1087 AD). It underwent maintenance and expansion through the Jin, Yuan, Ming, Qing, and Republic of China periods, continuously growing in scale and collection. In 1961, it was listed by the State Council as one of the first batch of Major Historical and Cultural Sites Protected at the National Level. It currently houses nearly 3,000 stone steles and epitaphs from the Han Dynasty to the present, with 1,089 on display. It boasts the largest collection of stone steles and epitaphs in China, with a complete chronological series spanning over 2,000 years. It is acclaimed as the "Treasure House of Eastern Culture," the "Source of Calligraphic Art," the "Hall of Exquisite Han and Tang Stone Carvings," and the "World's Oldest Stone Inscription Library," making it one of Xi'an's most valuable cultural relics. The city wall was built in the early Ming Dynasty on the foundation of the Tang Imperial City. Since its completion, the wall has undergone three major renovations. In the second year of the Longqing era of the Ming Dynasty (1568), Governor Zhang Zhi of Shaanxi oversaw repairs that transformed the earthen wall into a brick wall for the first time. In the 46th year of the Qianlong era of the Qing Dynasty (1781), Governor Bi Yuan of Shaanxi oversaw renovations to the wall and its gate towers. Since 1983, the Shaanxi Provincial Government and the Xi'an Municipal People's Government have carried out large-scale restorations of this ancient city wall, reconstructing the destroyed eastern gate, northern gate arrow towers, southern gate sluice tower, and drawbridge, and establishing the Ring Park, revitalizing this ancient structure and making it a major tourist attraction in Xi'an. The Guangmen, Zhuquemen, South Gate, Wenchangmen, Hepingmen, Jianguomen, and East Gate are all located in the Beilin District.

II. Historical Evolution

The Xi'an Ming Dynasty City Wall was built from the 7th to the 11th year of the Hongwu era (1374-1378) on the foundation of the Sui and Tang Imperial City. Designed around a "defensive" strategic system, the wall's thickness exceeds its height, making it as solid as a mountain, with a top wide enough for chariots and drills. Counting from the Sui and Tang Imperial City, the Xi'an ancient city wall has a history of over 1,400 years; from its expansion in the early Ming Dynasty, it has a history of over 600 years, making it one of the most completely preserved ancient city wall structures in China.

In the first year of the Tianyou era of the late Tang Dynasty (904), Han Jian, the military governor of the Youguo Army stationed in Chang'an, rebuilt the city due to its large size making it difficult to defend. During the Tianyou reconstruction, the outer city and palace city of Chang'an were abandoned, and only the imperial city was renovated. The Zhuque, Anfu, and Yanxi gates of the imperial city were sealed, and the Xuanwu Gate was opened to the north for better defense, but the city walls were neither expanded nor rebuilt. Subsequently, through the Later Tang, Later Jin, and Later Han of the Five Dynasties period, Xi'an was known as Fengyuan City, an important town in the northwest.

In the second year of the Hongwu era of the Ming Dynasty (1369), General Xu Da led his army across the river from Shanxi into Shaanxi. The Yuan defenders fled, and Xu Da occupied Fengyuan City. The Ming court changed Fengyuan Road to Xi'an Prefecture, marking the beginning of the name "Xi'an."

From the 3rd to the 11th year of the Hongwu era (1370-1378), the formal construction of the Xi'an city wall took place. The wall was built by compacting layers of loess. Parapets were built along the inner and outer edges of the wall top. The outer parapet had 5,984 crenellations, while the inner parapet had none. Along the outer wall, a mamian (a rectangular defensive platform) was built every 120 meters, totaling 98, each topped with a blockhouse. At each of the four corners of the wall stood a corner tower, with the southwestern one being circular.

In the second year of the Longqing era of the Ming Dynasty (1568), Governor Zhang Zhi of Shaanxi oversaw repairs, facing the outer wall and top surface with blue bricks, transforming the earthen wall into a brick wall for the first time.

In the ninth year of the Chongzhen era of the Ming Dynasty (1636), Governor Sun Chuanting of Shaanxi built earthen walls for the four outer city gates. There were four main gates: Changle Gate to the east, Anding Gate to the west, Yongning Gate to the south, and Anyuan Gate to the north. Each gate had a triple gate tower system: a sluice tower, an arrow tower, and a main tower. The sluice tower was outermost, the arrow tower in the middle, and the main tower innermost. The enclosed area between the arrow tower and the main tower formed the barbican. The entire wall constituted a严密 (tight) defensive system, with a wide moat outside the city.

During the Qing Dynasty, the Xi'an city wall underwent 12 repairs, the largest of which was overseen by Governor Bi Yuan of Shaanxi in the 46th year of the Qianlong era (1781). This project thickened the brick facing on the entire outer wall and built blue brick drainage channels every 40-60 meters along the inner wall to drain rainwater from the top.

After the Republic of China and the founding of the People's Republic of China, 12 new gates were opened: Chaoyang Gate and Zhongshan Gate to the east; Jiefang Gate, Shangwu Gate, and Shangde Gate to the north; Yuxiang Gate to the west; and Hanguang Gate, Wumu Gate, Zhuque Gate, Heping Gate, Wenchang Gate, and Jianguo Gate to the south.

III. Architectural Structure

The Xi'an city wall was entirely designed around a "defensive" strategic system. Its thickness exceeds its height, making it as solid as a mountain, with a top wide enough for chariots and drills. The wall is 12 meters high, 12-14 meters wide at the top, 15-18 meters wide at the base, with a circumference of 13.74 kilometers. There are four main gates: Changle Gate to the east, Anding Gate to the west, Yongning Gate to the south, and Anyuan Gate to the north. Each gate has a triple gate tower system: sluice tower, arrow tower, and main tower. The main tower is 32 meters high and over 40 meters long, featuring a hip-and-gable roof with upturned corners, triple eaves, and a surrounding corridor on the ground floor, presenting an antique, majestic, and grand appearance.

The city wall includes a series of military facilities: the moat, drawbridge, sluice tower, arrow tower, main tower, corner tower, blockhouse, parapet, and crenellations. At each of the four corners of the wall stands a corner tower, and outside the wall is the city moat. The outer side of the wall top is lined with battlements, also called crenellated walls, totaling 5,984, with embrasures for shooting arrows and observation. The inner low wall is called the parapet, without embrasures, to prevent soldiers from falling while walking. Every 120 meters along the wall, a blockhouse protrudes outward from the wall, its top level with the wall walkway. These were specifically designed to shoot enemies scaling the wall. The distance between blockhouses is such that half of it falls within the effective range of arrows, facilitating the shooting of attacking enemies from the side. There are 98 blockhouses in total on the wall, each topped with a garrison building.

The original Xi'an city wall was built by compacting layers of loess. The lowest layer was a mixture of earth, lime, and glutinous rice juice, making it exceptionally hard. Later, the entire inner and outer walls and top were faced with blue bricks. Along the top of the wall, drainage channels made of blue bricks were built every 40-60 meters, playing a crucial role in the long-term preservation of the ancient Xi'an city wall.

With ancient weapons being落后 (backward), the city gates were the only passageways, making them the focal point of defense meticulously managed by feudal rulers. Each of the four main gates of the Xi'an city wall has a triple gate tower system: main tower, arrow tower, and sluice tower. The sluice tower is outermost, used for raising and lowering the drawbridge. The arrow tower is in the middle, with square windows on the front and sides for shooting arrows. The main tower is innermost, with the main gate passage below it. The area between the arrow tower and the main tower, enclosed by walls, is called the barbican, used for stationing troops. Within the barbican are ramps leading to the top of the wall, gently sloped without steps for horses to ascend and descend. There are 11 such ramps throughout the city. At each of the four corners of the wall are corner platforms protruding outward. Except for the southwestern corner, which is circular (possibly preserving the original shape of the Tang Imperial City corner), the others are square. On these corner platforms stand corner towers, taller than the blockhouses, indicating their important role in warfare.

The Xi'an city wall had strong defensive capabilities. The moat outside the city was the first line of defense. The drawbridge over the moat was the only passage in and out. During the day, the drawbridge was lowered across the moat for passage; at night, it was raised, cutting off access to the city. Outside the city gate was the sluice tower (also called the watchtower), used for keeping night watch and sounding alarms, serving as the second line of defense. Behind the sluice tower was the arrow tower, over 30 meters high, with straight outer walls densely perforated with arrow slits, facilitating observation and shooting—the third line of defense. Between the arrow tower and the main tower was the barbican, covering 9,348 square meters. Its purpose was to trap enemies who breached this point, forming a "catch in a jar" situation—the fourth line of defense. The fifth line of defense was naturally the main gate itself.

In addition to the严密 (tight) defenses at the gates, corner towers were built on the corner platforms at the four拐角 (corners) of the wall to assist the gates in observing and defending against enemies from all directions. Along the entire outer side of the wall, every 120 meters, there is a mamian (also called a blockhouse). Each mamian is 20 meters wide, projecting 12 meters outward from the wall, with the same height and structure as the wall. The Xi'an city wall has 98 mamian and 5,984 crenellations, giving the outer wall a锯齿形 (sawtooth) appearance. On each mamian, there are three rooms for garrison troops (also called blockhouses). The wall and mamian have parapets with凹口 (recesses) and方孔 (square holes) for both concealment and observation/shooting.

IV. Gate Introductions

The Xi'an city wall currently has 18 gates. Starting from Yongning Gate and moving clockwise, they are: Yongning Gate, Zhuque Gate, Wumu Gate, Hanguang Gate, Anding Gate, Yuxiang Gate, Shangwu Gate, Anyuan Gate, Shangde Gate, Jiefang Gate, Shangjian Gate, Shangqin Gate, Chaoyang Gate, Zhongshan Gate, Changle Gate, Jianguo Gate, Heping Gate, Wenchang Gate. The formation times and specifications of these 18 gates vary.

Seven Southern City Gates

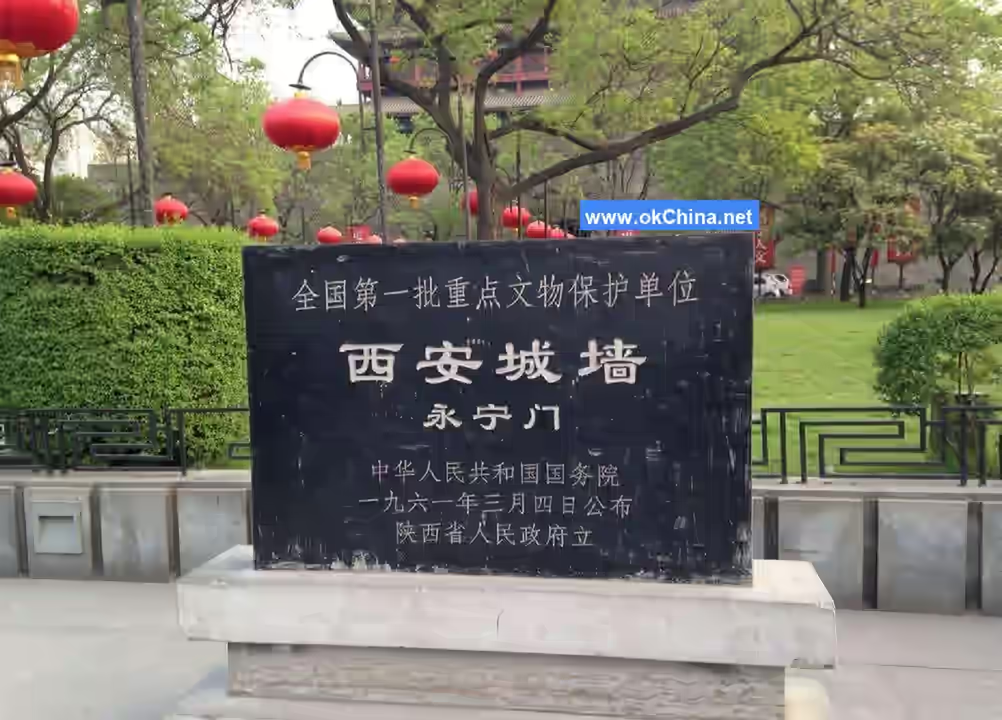

Yongning Gate

Yongning Gate, commonly known as the South Gate, is the oldest and longest-used gate among Xi'an's city gates, built in the early Sui Dynasty. It was the easternmost of the three southern gates of the imperial city, called Anding Gate. It was retained as the south gate when Han Jian缩建 (reduced and built) the new city in the late Tang Dynasty and renamed Yongning Gate in the Ming Dynasty. The arrow tower of Yongning Gate was destroyed during the Defense of Xi'an (also known as the Two Tigers Guarding Chang'an) and was rebuilt on the original site in 2013. Yongning Gate has a 6+1 gate passage configuration.

Zhuque GateThe Zhuque Gate was originally the main southern gate of the Tang Dynasty's Chang'an Imperial City, with the central Zhuque Avenue running beneath it. During the Sui and Tang dynasties, emperors often held grand ceremonies here. In the ninth year of the Kaihuang era (589 AD), after the Sui Empire unified the realm, Emperor Wen of Sui reviewed the triumphant army from the gate tower of Zhuque Gate. When Han Jian constructed the new city during the late Tang period, the Zhuque Gate was sealed. In 1985, during the restoration of the Xi'an city wall, the ruins of the Zhuque Gate, encased within the Ming Dynasty wall, were excavated. As described by Sui and Tang literati, it was grand and magnificent: the gate pillar bases were made of marble, the threshold of bluestone was carved with elegant and lively vine patterns, and the gate passage walls were thick and upright with finely fitted bricks. The Zhuque Gate opened in 1986 is located west of the ruins. The Zhuque Gate features four passageways.

Wumu Gate

The Wumu Gate, commonly known as the Small South Gate, was opened in the 28th year of the Republic of China (1939) and renamed Wumu Gate in the 36th year of the Republic of China (1947) in memory of Mr. Jing Wumu, a revolutionary martyr from Shaanxi in the 1911 Revolution. Jing Wumu was one of the earliest members of the Tongmenghui, a revolutionary of significant influence during the democratic revolution, who heroically sacrificed his life in the Constitutional Protection Movement. He was praised by Sun Yat-sen and Huang Xing as the "Giant Pillar of the Northwest Revolution." To commemorate the martyr, the Shaanxi military and civilians renamed Sifu Street, where Jing Wumu once lived in Xi'an, to "General Jing Street" in the 35th year of the Republic of China (1946), and named the gate at the southern end of the street "General Jing Gate." In the 36th year of the Republic of China (1947), they were renamed "Wumu Street" and "Wumu Gate," respectively. The Wumu Gate features a single passageway.

Hanguang Gate

The Hanguang Gate is the westernmost gate on the southern city wall and was the western side gate on the southern side of the Tang Dynasty's Chang'an Imperial City. When Han Jian constructed the new city during the late Tang period, the central and western passageways were sealed, while the eastern passageway was retained. After the Northern Song Dynasty, all passageways were sealed. During the renovation of the Xi'an city wall in 1984, the ruins of the Hanguang Gate were excavated, revealing pillar bases made of granite and carved thresholds and gateways. New arched gate passages were built on the east and west sides of the ruins, with the ruins protected by a frame structure and covered with city bricks to match the appearance of the wall. Artificial lighting and air conditioning systems were installed inside for visitors. The Tang Imperial City Wall Hanguang Gate Ruins Museum can be accessed from the city wall. The Hanguang Gate features four passageways.

Jianguo Gate

The Jianguo Gate is the easternmost gate on the southern city wall. It was newly opened in the Jianguo Road section of the southern city wall to commemorate the great historical event of the founding of the People's Republic of China, hence the name Jianguo Gate. Although Jianguo Road is short, it carries profound historical significance. According to historical research, the famous Tang Dynasty minister Zhangsun Wuji lived in what is now Jianguo Road. During the Republic of China period, the Xi'an Incident, which shocked China and the world, involved General Zhang Xueliang, whose residence was located here. Today, Zhang Xueliang's residence has been designated as a national key cultural relic protection unit. The Jianguo Gate features three passageways.

Heping Gate

The Heping Gate lies on the same north-south axis as the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda, Dachashi, Xi'an Railway Station, and the Hanyuan Hall of the Daming Palace. It was opened in 1953. To express the Chinese people's longing for world peace after enduring years of war, it was named Heping Gate. Inside the gate is Heping Road, and outside is Yanta Road. The Shuncheng Lane paved with bluestone slabs, stretching west from inside the Heping Gate to the Wenchang Gate, is known as Xiamaling. Over 2,100 years ago, even Emperor Wu of Han had to dismount and walk when passing through here because the famous politician Dong Zhongshu was buried here, giving the place its name. The Heping Gate features four passageways.

Wenchang Gate

The Wenchang Gate is located north of the Stele Forest Museum and was opened in 1986. A Kuixing Tower was built on the city wall here, the only facility on the Xi'an city wall unrelated to military defense. Kuixing, also known as "Kui Star" or "Kui Constellation," is one of the twenty-eight constellations and is said to be the deity governing literary fortunes, revered as the "Star of Literature" or "Wenchang Star." If touched by his red brush, one could write with divine skill, pass imperial examinations at all levels, and become a top scholar. Therefore, ancient Confucian temples and schools often had Kuixing Towers for incense offerings. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the Xi'an Prefectural School and Confucian Temple were built near the city wall (now the Stele Forest Museum), and the Kuixing Tower was accordingly built on the wall. The Kuixing Tower was restored in 1986, and the newly opened gate beneath it was named Wenchang Gate. The Wenchang Gate features four passageways.

Two Gates on the Western Wall

Anding Gate

The Anding Gate, commonly known as the West Gate, is the southernmost gate on the western city wall and was originally the central gate on the western side of the Tang Imperial City. During the Ming Dynasty expansion of the city wall, its position was slightly moved southward, and it was named Anding Gate, symbolizing peace and stability in the western frontier. This gate originally had three gate towers: the main gate tower, the archery tower, and the sluice gate tower. There were three layers of walls: the main gate tower inside, the archery tower in the middle, and the sluice gate tower outside. Each tower had arched gate passages, each 6 meters high and wide. Between the main gate tower and the archery tower was a square barbican, serving as an entrance and exit passage in peacetime and a defensive stronghold in wartime. North of the main gate tower is an observation platform built during the Japanese Emperor's visit to Xi'an, open to visitors and designated as a national key cultural relic protection unit. The West Gate archery tower is the most completely preserved ancient castle in China to date. Inside the gate is West Street, and outside is West Guan Zheng Street. The Anding Gate features a 6+1 passageway layout.

Yuxiang Gate

In the 15th year of the Republic of China (1926), Liu Zhenhua, a henchman of Wu Peifu and a warlord from Henan, besieged Xi'an for eight months, causing over 40,000 deaths from cold, starvation, and war. It was not until General Feng Yuxiang led the National Allied Forces to defeat Liu Zhenhua that Xi'an was relieved. In the 17th year of the Republic of China (1928), this gate was built on the breach opened during the war. To commemorate General Feng's historical achievement of leading his troops into the city through this breach, it was named Yuxiang Gate, the northernmost gate on the western city wall. The Yuxiang Gate features five passageways.

Six Gates on the Northern Wall

Shangwu Gate

The Shangwu Gate is the westernmost gate on the northern city wall of Xi'an, opened after the founding of the People's Republic of China. Inside the gate is Northwest Third Road, and outside is Gongnong Road. The Shangwu Gate features four passageways.

Anyuan Gate

The Anyuan Gate, commonly known as the North Gate, was built during the Ming Dynasty construction of the city wall. The name "Anyuan" inherits the policy of appeasement and pacification adopted by the Central Plains Han court towards remote ethnic minorities, hoping they would submit to the court out of gratitude. During the 1911 Revolution, when the insurgent army attacked the Qing Dynasty, fierce battles took place at the Anyuan Gate, and the North Gate tower was burned down in the fighting. During the 1983 renovation of the city wall, the original archery tower was restored. The Anyuan Gate features a 4+1 passageway layout.

Shangde Gate

The Shangde Gate is located east of the Anyuan Gate and was opened after the founding of the People's Republic of China. In the 16th year of the Republic of China (1927), during the "New Life Movement" advocating the "Four Virtues and Eight Principles," the north-south streets from east to west were named after the "Four Virtues" of "Diligence, Frugality, Benevolence, and Virtue," prefixed with "Shang," resulting in Shangqin Road, Shangjian Road, Shangren Road (later renamed Zhongzheng Road, now Jiefang Road), and Shangde Road. After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, three gates were opened on the northern city wall at Shangqin Road, Shangjian Road, and Shangde Road, named Shangqin Gate, Shangjian Gate, and Shangde Gate, respectively. The Shangde Gate features three passageways.

Jiefang Gate

In the 21st year of the Republic of China (1932), with the opening of the Longhai Railway, a gate was opened on the northern city wall at Shangren Road, named Shangren Gate. In the 34th year of the Republic of China (1945), Shangren Road was renamed Zhongzheng Road, and the gate was renamed Zhongzheng Gate. In 1950, Zhongzheng Road was renamed Jiefang Road, and the gate was renamed Jiefang Gate. In 1952, it was demolished due to the expansion of the railway station square, becoming a breach in the Xi'an city wall. In 2005, it was reconnected with a large-span arched gate, completing the Xi'an city wall circuit. The Jiefang Gate features a large-span arched design with three passageways.

Shangjian Gate

The Shangjian Gate is located between the Jiefang Gate and the Shangqin Gate on the northern city wall and was opened after the founding of the People's Republic of China. After the founding of the People's Republic of China, a gate was opened on the northern city wall at Shangjian Road, named Shangjian Gate. Inside the gate is Shangjian Road, and outside is the East Roundabout of the Railway Station. The Shangjian Gate features three passageways.

Shangqin Gate

The Shangqin Gate is the easternmost gate on the northern city wall, opened after the founding of the People's Republic of China. In 1949, after the founding of the People's Republic of China, three gates were opened on the northern city wall at Shangqin Road, named Shangqin Gate. Inside the gate is Shangqin Road, and outside it forms a T-junction with Huancheng North Road. The Shangqin Gate features three passageways.

Three Gates on the Eastern Wall

Chaoyang Gate

The Chaoyang Gate is the northernmost gate on the eastern city wall, opened after the founding of the People's Republic of China. Because this gate faces the sun and is the first to see sunlight each day, it was named Chaoyang Gate. Inside the gate is East Fifth Road, and outside is Changle Road. The Chaoyang Gate features five passageways.

Zhongshan Gate

The Zhongshan Gate, commonly known as the Small East Gate, was opened in early 1927 at the suggestion of General Feng Yuxiang and named in memory of the national revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen. On May 1, 1927, General Feng Yuxiang led his troops eastward from the Zhongshan Gate. The Zhongshan Gate has two parallel passageways, which Feng named "Dongzheng Gate" (East Expedition Gate) and "Kaixuan Gate" (Triumphal Return Gate). On the day of departure, Feng Yuxiang addressed the crowd from the city wall, saying that when the Northern Expedition succeeded, he would open the Kaixuan Gate to welcome him back. However, due to changing circumstances, he never led his troops back to Xi'an. The Zhongshan Gate features two passageways.

Changle Gate

The Changle Gate, commonly known as the East Gate, is the main gate on the eastern city wall and the southernmost gate. It was constructed during the Ming Dynasty wall building and officially named Changle Gate. At the end of the Ming Dynasty, Li Zicheng entered Xi'an through the East Gate. Seeing the plaque "Changle Gate" hanging on the gate, Li Zicheng said to his soldiers, "If the emperor is to have eternal joy, the people will suffer eternally." His subordinates then set fire to the gate tower, which was not rebuilt until the Qing Dynasty. Before the "Xi'an Incident," General Zhang Xueliang organized training teams and student soldier teams on the East Gate tower. The site has been restored as a memorial to the Xi'an Incident. The Changle Gate features a 6+1 passageway layout.

Architectural Features

Horse Ramp for Ascending the WallThe city wall rises above ground level, requiring access points to connect the upper and lower sections. These access points are the horse ramps and stairways built along the wall. During the Ming Dynasty, Xi’an City had a total of eleven horse ramps for ascending the wall, seven of which were built along the inner side of the wall, and four located to the left of the gate towers within the four city gates.

The seven horse ramps built along the inner side of the wall were all constructed with brick and designed as rolling slopes. On the inner right side of each ramp, there was a 1.5-meter-wide stairway for infantry to ascend and descend. The horse ramps had a slope of 25 degrees, a width of 6 meters, and a height level with the top surface of the wall, adhering closely to the inner wall. They featured dual staircases on both sides, forming an isosceles trapezoid shape with a base length of 100 meters and a top length of 10 meters. Protective walls were built alongside the ramps, and gates were installed at the lower entrances. These gates, painted bright red, were known as "Big Red Gates" and were guarded by stationed troops.

Top Surface of the Wall

The top surface of the wall refers to the flat plane at the summit of the city wall. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, great importance was placed on protecting the wall and reinforcing its top surface. In the second year of the Longqing era of Emperor Muzong of the Ming Dynasty (1568), Zhang Zhi, the Governor of Shaanxi, oversaw the laying of bricks on the outer surface of Xi’an’s earthen wall and also paved the entire top surface with blue bricks. In the 46th year of the Qianlong era of the Qing Dynasty (1781), Governor Bi Yuan of Shaanxi led the renovation of Xi’an’s city wall, during which the entire top surface was repaired and modified. To facilitate movement on the wall and prevent rainwater from soaking the top, a 0.45-meter-thick layer of mixed earth was first added and compacted on the surface, followed by two layers of flat-laid bricks. The entire top surface was uniformly sloped inward at approximately 5 degrees to allow rainwater to drain quickly into the water channels on the inner side of the wall.

Water Channels

Water channels are drainage structures on Xi’an’s city wall, constructed under the supervision of Governor Bi Yuan of Shaanxi during the 46th year of the Qianlong era of the Qing Dynasty. These channels are made of brick and stone, attached to the inner wall of the city, extending vertically from the top to the base. They feature stone spouts, with channel openings 0.65 meters wide and 0.70 meters deep. The walls of the channels are brick-lined, each 0.60 meters thick. Below the wall, drip stones connect to drainage ditches. Rainwater enters through the spouts at the top, flows down the channels, disperses at the drip stones, and then drains into underground sewers. The channels are spaced 40–60 meters apart, with a total of 167 built along the inner wall. The construction of these water channels prevented the wall from being damaged by rainwater soaking, playing a crucial role in its preservation.

Parapets

Parapets refer to the thin protective walls built along the inner and outer edges of the city wall’s top. Compared to the main wall, they are much smaller, hence the name "parapets." Those built along the inner edge are also called "inner parapets," while those on the outer edge are called "battlements." Parapets serve as protective barriers and defensive structures on the wall’s top, essential features of ancient city walls.

The top of Xi’an’s Ming Dynasty city wall had parapets along its outer edge. The inner parapets were 0.75 meters high and 0.45 meters thick. The outer battlements were 1.75 meters high, 0.45 meters thick, and 2.35 meters long, with gaps of 0.6 meters between them, known as "crenels."

The battlements on Xi’an’s Ming Dynasty wall were arranged in a "pin" shape, with a square outer and round inner opening measuring about 0.29 meters high and wide, used for observation and shooting. Openings were also left at the base of the battlements for firing weapons such as the "Folangji" cannon (a Ming imitation of Portuguese cannons) and hand cannons. The tops of the battlements and crenels were capped with "mountain"-shaped bricks to defend against grappling hooks and scaling ladders used by enemies. However, this "pin"-shaped design with openings was not very sturdy and could be easily pulled down by attackers.

Most of the inner parapets and battlements on Xi’an’s city wall were dismantled or damaged before and after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. In 1983, the Xi’an City Wall Construction Committee carried out comprehensive restoration, preserving the design from the Qing Dynasty renovations overseen by Bi Yuan.

Crenels

Crenels refer to the gaps between the battlements along the outer edge of the city wall’s top. On Xi’an’s Ming Dynasty wall, the 0.6-meter gaps between battlements served as crenels, designed for observation and shooting as part of the wall’s defensive engineering. Xi’an’s city wall has a total of 5,984 crenels.

At the corners of Xi’an’s Ming Dynasty wall, the battlements did not have gaps but followed the corner’s shape, forming a right angle. These were called "corner battlements," while ordinary battlements were called "straight battlements." For example, the protruding sections of the wall, such as the "horse faces" and barbicans, had battlements that followed their contours. Straight sections had straight battlements, while outer and inner corners had corner battlements. For instance, a horse face on the southern wall had seven full battlements, two corner battlements, and seven spear holes on the front, and two full battlements, two corner battlements, and four spear holes on the side. Between two horse faces, there were 39 full battlements, 39 spear holes, and two corner battlements, totaling 54 battlements per section. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the Xi’an Municipal Government carried out comprehensive restoration of the crenels.

Moat Surrounding the City

Outside Xi’an’s Ming Dynasty city wall, a moat encircled the city, forming part of its defensive system alongside the wall. The moat, also known as the city river, sometimes remained dry and was referred to as a "dry ditch" or "trench." The Ming Dynasty moat around Xi’an was over 14 kilometers in circumference. The distance between the main wall and the moat was about 28 meters, while the protruding horse faces were only about 10 meters from the moat. The width of the moat varied because it was not a dry ditch but a water channel, with a fixed elevation at the bottom and varying depths along the top depending on the terrain. The deepest sections were in the south, while the northern sections were shallower. The widest part of the southern moat measured about 45 meters.

This scale of Xi’an’s moat was the result of renovations over multiple dynasties. The Han Dynasty Chang’an city was already surrounded by a moat. The Tang Dynasty Chang’an city also had a moat, but the imperial city within had no river. At the end of the Tang Dynasty, Han Jian rebuilt the imperial city into a new city and began constructing a moat around it. This city was used through the Five Dynasties, Song, Jin, and Yuan periods, with multiple dredging and water diversion projects. During the early Ming Dynasty, the city was expanded, and the moat was extended accordingly. The Qing Dynasty carried out multiple dredging, widening, and deepening projects on the Ming moat.

Corner Platforms

Xi’an’s city wall is rectangular, with corner platforms at the four corners—solid platforms protruding from the wall at the turns. Among the four corners, the southeast, northeast, and northwest corners are right angles, with square corner platforms. The northwest square platform measures 25 meters per side, rises 1.9 meters above the wall top, and protrudes 11 meters from the wall. The northeast square platform measures 21.5 meters per side, rises 1.9 meters above the wall top, and protrudes 11 meters from the wall. The southeast square platform is similar in design. The southwest corner platform is uniquely circular, with a top diameter of 20 meters and a height 1.9 meters above the wall. All four corner platforms of Xi’an’s city wall are well-preserved today.

Corner Towers

Corner towers are pavilion-like structures built on corner platforms, serving as important defensive facilities on the city wall. Like watchtowers, corner towers protrude outward from the wall, providing a broad field of view for observing enemy movements. During wartime, soldiers stationed in corner towers could fire arrows and weapons from the front and coordinate with adjacent watchtowers and wall defenders to create crossfire, effectively repelling attackers. The architectural styles of the four corner towers on Xi’an’s Ming and Qing Dynasty walls were not identical. The remains of the northwest square corner tower measured 7.30 meters per side, with seven foundation stones, each 0.42 meters in size and spaced 3.86 meters apart.

The corner tower on the northeast square platform was octagonal, with each side measuring 5.1 meters. Its remains included six foundation stones, each 0.42 meters in diameter. The corner tower on the southwest circular platform was also octagonal, with each side measuring 3.2 meters. Its remains included 16 foundation stones, each 0.40 meters in diameter and spaced 1.5 meters apart. Due to prolonged warfare, all four corner towers on Xi’an’s Ming and Qing Dynasty walls were destroyed. Since 1983, the Xi’an City Wall Construction Committee has restored and rebuilt the corner towers on the southeast, northeast, and northwest corner platforms.

Watch Platforms

Watch platforms, also known as墩台,墙台, or "horse faces," are structures protruding from the wall for three-sided defense, serving as key defensive points along the wall’s perimeter. On Xi’an’s Ming and Qing Dynasty walls, watch platforms were built every 120 meters extending from the gates, each protruding 20 meters from the wall, 12 meters wide, and level with the wall top. There were 98 such platforms in total: 20 on the eastern and western walls each, and 29 on the southern and northern walls each. The outer three sides of the platforms had battlements, with crenels on the left and right sides. The crenels were about 0.44 meters wide, allowing defenders to throw bricks, stones, and logs or fire arrows and projectiles to repel attackers. The front battlements had no crenels and were about 0.64 meters higher than the side battlements to protect defenders from projectiles. The platforms were spaced 120 meters apart, with overlapping fire coverage at 60 meters—the effective range of ancient bows, crossbows, grappling hooks, and throwing spears. This design created a dense crossfire network from the front and sides of the platforms, making it difficult for enemies to approach the wall and enhancing its defensive capabilities.

Of the 98 watch platforms built during the early Ming Dynasty in Xi’an, 89 remained by 1982, with nine destroyed. Since 1983, the Xi’an City Wall Construction Committee has restored four platforms, bringing the total to 93.

WatchtowersThe watchtower is a tower built on the defensive platform of an ancient city wall. The Ming-era Xi'an City Wall has ninety-eight protruding defensive platforms, each with a watchtower built on it, totaling ninety-eight. The watchtowers on the Ming-era Xi'an City Wall are all two-story structures with a hip-and-gable roof and double eaves. As buildings constructed along the top of the city wall, watchtowers were used during wartime for city defense, providing command, observation, and communication posts for garrison troops, as well as storage for weapons and supplies. In peacetime, they served as shelters for patrolling soldiers to rest and take cover from wind and rain. They are a type of facility designed to enhance the defensive capabilities of the city wall.

Starting in 1986, the Xi'an City Wall Construction Committee began rebuilding the watchtowers destroyed during the Ming Dynasty. By the end of 1989, twelve watchtowers had been reconstructed, including seven on the southern wall and five on the eastern wall. In 2006, six additional watchtowers were built on both sides of the southwestern corner and the northern gate. The reconstructed watchtowers, following the original Ming design, are two-story structures with a hip-and-gable roof, double eaves, and a brick-and-wood framework.

Arrow Tower

On the outer side of the arrow tower, the part higher than the city wall is the eave wall. At the top of the eave wall, where it meets the purlin, a layer of brick eaves projects outward as a decorative transition. The projecting part of the brick eaves is about 10 centimeters long. The outer eave wall of the arrow tower is densely perforated with arrow windows for defensive counterattacks. The front side has four layers of arrow windows, with twelve windows per layer, totaling forty-eight windows. The side walls on the left and right of the arrow tower are also made of brick. The lower level has no windows, while the upper part has three layers of arrow windows, with three windows per layer, totaling nine windows on each side, or eighteen windows combined. Thus, the entire arrow tower has sixty-six arrow windows on its three sides.

The lower level of the side walls has no windows because these walls are situated on the city wall. This design allows defenders to retreat into the arrow tower for resistance if the enemy breaches the wall. If there were windows on the lower level, they would be too close to the ground and could be exploited by attackers who have scaled the wall.

Inside, the arrow tower has four floors, corresponding to the four layers of defensive windows on the exterior. The floors are connected by stairs, allowing soldiers to ascend to each level and engage in defensive combat from the windows. Defenders can observe the outside from these windows and launch counterattacks. If all forty-eight windows were to fire crossbow arrows simultaneously, they would create significant杀伤力. The arrow windows are equipped with small wooden doors that can be closed for protection against arrows during danger. Iron hooks are installed above the windows, and bolts are placed behind them to secure the closed windows.

Kuixing Tower

Approximately 667.5 meters east of the southern gate tower of the Xi'an City Wall stands a Kuixing Tower, dedicated to the deity Kuixing, who is believed to govern literary fortunes. The tower was first built in the ninth month of the year 1619 during the Ming Dynasty but was later destroyed by war. Although it was rebuilt during the Qing Dynasty, neither the Ming nor Qing structures have survived. The tower seen today was restored in 1986. It features a platform-based structure with double eaves and a pyramidal roof, standing 14.65 meters tall with a side length of 9.4 meters. The first floor of the tower has a side length of 3.5 meters and a height of 6.1 meters, while the second floor has a side length of 3.5 meters and a height of 5.5 meters, adorned with painted decorations.

According to the Cihai, the term "Kuixing" first refers to the first four stars of the Big Dipper, also known as "Xuanji." These four stars form a square shape resembling a dipper, which ancient people called a "soup ladle." Hence, the Shuowen explains, "Kui means a soup ladle." These four stars are also referred to as "Kuixing" or "Doukui." Because Kuixing is believed to have divine authority over literary fortunes, Kuixing Towers were built near Confucius Temples and prefectural schools after the Song and Yuan dynasties for scholars to worship.

Barbican

The barbican is a small fortification built outside the city gate to shield the barbican gate and control the drawbridge over the moat. The barbican of Xi'an City was built in the late Ming Dynasty and destroyed in the early Republic of China era. It faced the moat in front, backed against the barbican gate, and was rectangular in shape, smaller and lower than the barbican gate. The center of the barbican's front wall featured an arched gateway, above which a gate tower was built. The barbican had walls on its eastern, southern, and northern sides, which were about one-third shorter than the walls of the barbican gate. These walls were topped with parapets and connected to the front wall of the barbican gate on both sides. The barbican was the first line of defense for those crossing the drawbridge over the moat to enter the city gate, making it a crucial structure in the city's defensive engineering.

Gate Tower

The gate tower is built above the arched gateway of the barbican. It derives its name from its role in controlling the drawbridge, which acts as a "gate" over the moat, a必经之路 for entering the city. The gate tower is also called a炮楼 because it housed soldiers and stored firearms and cannons to封锁 the entrance通道 and eliminate enemies attacking the gate. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, gate towers were built on the barbicans of all four city gates. In the early Republic of China era, bridges were constructed over the moat outside the city gates to facilitate transportation, leading to the complete demolition of the barbicans and gate towers. The current gate tower at the southern gate of Xi'an has been reconstructed according to the Ming Dynasty's original design.

In 1989, the reconstructed southern gate tower, following the old design, was built above the barbican's gateway. The tower body is entirely constructed of blue bricks. It is three bays wide, two stories high, and features a悬山式 roof. The front side has two rows of arrow windows, with six windows per row. The side walls each have two rows of arrow windows, with two windows per row, totaling twenty arrow windows. The inner side of the upper floor has twelve wooden windows, with a door in the middle of each floor and five wooden windows on each side.

Barbican Gate

The barbican gate is a semicircular or square protective小城 built outside a city gate (with rare exceptions inside the gate) to strengthen the defense of a fortress or pass. It is part of ancient Chinese city walls. The barbican gate is connected to the city wall on both sides and equipped with defensive facilities such as arrow towers, gate barriers, and battlements. The gate of the barbican is usually not aligned with the city gate it protects, to prevent direct attacks by weapons like battering rams. Even if enemies breach the barbican, defenders can居高临下 from the arrow towers and surrounding walls, using密集的高空火力网 to trap and eliminate them within the barbican, ensuring the city gate remains secure—a strategy often described as "catching a turtle in a jar."

The barbican gate is a system of双重门, meaning a small enclosed area is built against the city wall outside the gate, with its own gate, creating a防御结构 of two consecutive gates. Outside the four gates of Xi'an City—east, south, west, and north—there is a square barbican gate. The four barbican gates share the same design and similar dimensions, demonstrating整齐规范. The outer wall of the barbican gate has a base width of approximately 97 meters, protruding about 76 meters from the city wall, covering an area of over 7,000 square meters. All four barbican gates are rectangular along the city wall direction, with内部围成的空间 roughly similar, typically about 48 meters wide and 65 meters long at the base. This type of structure, which背依城墙突出于城外, lies between two gates, is enclosed on all sides, and forms an open space inside, is the barbican gate.

V. Historical Value

First, the Xi'an City Wall is a wordless history book.

Xi'an is one of the world's four ancient capitals, having served as the capital for the most dynasties and the longest duration in Chinese history. During the Sui and Tang dynasties, Chang'an was the only国际化大都市 in the world with a population exceeding one million. The area enclosed by its city walls was seven times larger than Rome at the time and more than twice the size of Beijing, which became China's capital over a thousand years later. It was not until the late Tang Dynasty, with the decline of the Li Dynasty, that Chang'an abandoned its outer city walls and palace city during reconstruction, only renovating the imperial city, significantly reducing its scale.

The existing Xi'an City Wall was built between 1374 and 1378 during the Ming Dynasty, on the foundation of the Tang Dynasty's imperial city. Thus, the history of this Ming-era wall can be traced back to the predecessor of Tang Chang'an—the Sui Dynasty's Daxing City, constructed in the 6th century under the supervision of the great architect Yuwen Kai. It provides a historical载体 that can be read, analyzed, and appreciated across millennia of Chinese history.

When the Ming-era Xi'an City Wall was first built, it had only four gates: east, south, west, and north, named Changle, Yongning, Anding, and Anyuan, reflecting people's aspirations for平安 and快乐生活. The gates opened in the 1920s and 1930s, such as Zhongshan Gate, Yuxiang Gate, and Wumu Gate, were named after outstanding revolutionary pioneers. The many gates opened after the founding of New China, named和平 and建国, also bear distinct时代特征. The revival of Tang Dynasty gate names like Zhuque and Hanguang reflects cultural传承.

Second, the Xi'an City Wall is a prominent symbol of the ancient city.

Like people, cities must have their own distinct personalities. As a历史文化名城, Xi'an's鲜明的城市个性 is largely embodied in its urban architecture.

In the process of urban development, demolishing old buildings is quite normal. However, many old buildings are珍贵的历史遗存 with significant cultural value and should not be indiscriminately destroyed. Valuable old buildings must be carefully preserved. Xi'an's efforts in this regard are far from perfect, but it has, after much difficulty, preserved the完整的明城墙, making it a醒目标志 of ancient Xi'an.

Third, the debate over the preservation or demolition of the Xi'an City Wall is a试金石 for measuring the level of modern civilization.

The debate over the preservation or demolition of the Xi'an City Wall, which occurred more than half a century ago, actually showcased the different境界 and修养 of two groups of people with opposing views.

During the Great Leap Forward, calls to demolish the Xi'an City Wall grew increasingly loud. After failing to persuade the then municipal leaders of Xi'an in person, cultural heritage workers escalated their appeal to the State Council for intervention. On September 29, 1959, Xi'an received the "State Council Notice on the Protection of the Xi'an City Wall." On December 28, Xi'an Mayor Liu Geng signed a document stating, "From this day forward, it is strictly forbidden to remove city bricks, excavate city soil, or engage in any other activities that damage the city wall." This document saved the critically endangered wall, allowing it to narrowly escape destruction. On March 4, 1961, the Xi'an City Wall was finally announced by the State Council as one of the first batch of全国重点文物保护单位.The current Xi'an City Wall is the best-preserved ancient city wall in China, and we should pay high tribute to the insightful individuals who have worked to preserve it. When faced with the debate over whether to preserve or demolish the Xi'an City Wall—a litmus test for the level of modern civilization—they demonstrated their remarkable integrity.

Fourth, the Xi'an City Wall is a tangible embodiment of the collective urban memory of its citizens.

Throughout its long history, the Xi'an City Wall has witnessed intense battles during the "Two Tigers Defending Chang'an," bombing by Japanese aircraft during the War of Resistance Against Japan, the devastating scars left during the Great Leap Forward, the scenes of citizens volunteering to repair the wall in the 1980s, and today's events such as the Xi'an City Wall International Marathon, national Hanfu wedding ceremonies, and the acclaimed "Drunk Chang'an—Grand Tang Welcome Ceremony," known as the "World's First Etiquette." These urban memories are tightly intertwined with the tangible cultural heritage of the city wall, forming a rich historical and cultural treasure.

Comments

Post a Comment